| Previous | Contents | Next |

wot i red on my hols by alan robson (hilaris kirihimete)

Christmas Happiness is a Buy Product of Prosperity

The literati have a snobbish tendency to look down upon the various classes of genre fiction on the somewhat specious grounds that simple story telling is, by definition, shallow and therefore can contain few, if any, insights. Readers of genre fiction have the equally annoying habit of sneering at so-called literary fiction on the grounds that it is boring and often pretentious. I can’t help but notice in passing that phrasing the idea in this way strongly implies that literary fiction should therefore be treated like a genre in its own right! Oxymoronically, that suggests that perhaps the literati should actually hate the very thing that they profess to love! Anybody want to volunteer to shave the barber?

Both sides of the argument have some merit, but it’s so easy to find counter examples that I can’t help wondering about the state of dress (or undress) exhibited by the Emperor on any given day. Catch-22 and Lord of the Flies are undeniably works of great literary merit, but they are also very popular genre novels. And Terry Pratchett’s Discworld fantasies are huge best sellers that are stuffed full of thoughtful wit and sophisticated insight. So much so, in fact, that Pterry has often been accused of committing literature by some of his more aggrieved fans who seem to think that involves some degree of selling out to the establishment. Indeed, there is a whole book (Terry Pratchett: Guilty of Literature by Andrew M. Butler) which examines the question in great depth.

So what can we deduce from this paradox? In my own field of computer programming, there is a saying known as Zawinski's Law of Software Envelopment which states that "Every program attempts to expand until it can read mail. Those programs which cannot so expand are replaced by ones which can". The phenomenon is sometimes referred to as creeping featurism (or, more wittily, as feeping creaturism) and it refers to the practice of continually stuffing new features into software systems until the bare bones of the original functionality can scarcely be seen at all any more, and the program has turned into something completely different. It is my contention that the same phenomenon can be observed in many examples of genre fiction – genre writers often become more sophisticated as they become more prolific until eventually they mature and, like Terry Pratchett, start to become guilty of literature. (Pterry’s early novels were fairly run of the mill. It was only later in his career, when he became more proficient at his art, that his literary merit came to the fore.)

So Zawinski's Law of Literary Envelopment might therefore be formulated as "Every author attempts to expand their technique until they can write works of literary merit. Those authors who cannot so expand themselves are replaced by ones who can". In other words, it seems to me that those who look down on genre fiction haven’t really thought their position through.

All of which is my justification for introducing you to the novels of John Hart, a writer of the most extraordinary literary thrillers. He’ll give you a rattling good yarn that will keep you on the edge of your seat and make you postpone your bedtime, if that’s what you are looking for. But he’ll also make you think deep thoughts if you happen to be in the mood for pondering on such things. That’s a lot of balls to keep juggling in strangely complicated patterns through the air, but he never drops any of them on his foot and his novels are supremely satisfying, whichever side of the literary fence you build the hill you want to die on. So sit back, relax and just enjoy the words.

Down River is set in a small town in North Carolina. Five years before the events described in the novel, Adam Chase had been accused of murder. He was brought to trial and acquitted, leaving him free to carry on with his life. But to many people in the town accusation is synonymous with guilt and they continue to harass and persecute him to such an extent that he is forced to leave. He goes to live in New York, seeking anonymity in the big city. To a large extent, he succeeds. Out of sight is out of mind. But events conspire to bring him back home, though he knows there will be no forgiveness. Within hours of his return, he has been beaten up and his car has been vandalised. Not long after that dead bodies start to turn up and of course everyone believes that Adam has killed them…

Adam does have a violent streak, that is undeniable. But he also has a conscience and he genuinely tries to reconnect with the family who disowned him, the town that condemned him, and the woman who he loved and lost. But the new crop of murders makes success seem unlikely.

Of course, I was absolutely convinced that I knew who the real murderer was. Unfortunately for my theory, that character turned up murdered about half way through the story, which left me floundering a bit. The revelations, when they finally came, came thick, fast, and furious. Just when I thought I understood everyone’s motives, another rabbit got pulled out of the hat and I realised I hadn’t understood anything at all. The twists and turns will take your breath away.

As a thriller, the novel can’t be faulted. The plot is complex, clever, believable and red-herringed up to the eyeballs. Who could ask for anything more? And yet there is more, a lot more. Over and above the sheer mechanics of the plot, the story is about estrangement and about the odd ways that family dynamics work to present a united front even when (perhaps especially when) the individuals despise each other. Is forgiveness possible? Yes, particularly when everyone involved has their own dark secrets. Adam Chase may have the appearance of guilt (and he’s certainly not wholly innocent), but he’s definitely not alone either. His personality is not unique, he’s just been unlucky in the way it has affected him. And on a broader scale, the story also has a lot to say about the motivating power of greed and the necessity for revenge. Nobody gets off scot-free.

None of which would mean very much if the reader doesn’t sink into the world that the novel presents. I have absolutely no experience of living in small town America so I cannot say whether or not the picture that John Hart paints bears any resemblance to reality. But I can say that I found it completely convincing. These people, their lives and their problems were very real to me. I cared about them (well, most of them. Some of them I detested – but that’s just another sort of caring, isn’t it?). That very real emotional involvement with the story is what kept me reading all the way to the bitter-sweet end.

And if that’s not a tour-de-force of skilful writing, I don’t know what is.

Iron House is, if possible, even better than Down River. Michael and Julian are brothers. They were found abandoned when they were very young and they have grown up together in the Iron House orphanage. Michael has always been Julian’s protector – Julian is sickly and weak, a natural target for bullies. Following the death of one of the bullies, Michael runs away from the orphanage and Julian is adopted into a rich and, superficially at least, loving family. Over the course of the next twenty years Julian becomes a very successful author of rather dark children’s books (the insecurities of his early life have not gone away). Michael becomes the protégée of powerful gangster. He turns into an efficient killer, an enforcer, much feared by everyone. But now the gangster is an old man and he is dying. Michael knows that when the old man is finally dead his own life will be in danger from the men who want to carve up the old man’s empire. And then an unfortunate event takes place on the other side of the country which means that once more Julian needs Michael’s protection. That consideration has to take precedence over all other things…

Socrates told us that an unexamined life is not worth living, and that is the theme of Iron House. Michael is forced into it, of course, because the death of his patron leaves him dangerously exposed. He’s sure he can cope in the short term – none of his immediate enemies have his somewhat dubious skills – but he’s not sure he wants to any more. The old man has left him a way out. All he has to do is find the time to take it. But Julian needs him and, just as he always did when they were children, Michael finds himself in the position of trying to make things better. In order to do that, he needs to understand how Julian got into the dark place that he no longer seems able to crawl out of. He’s rich, famous and successful, but he remains fragile. As Michael re-visits their mutual past he finds uneasy echoes in their mutual present. Julian’s foster parents are not all that they seem to be. They too have dark secrets, lives that need examining. And of course there’s the really big question lurking behind all of this – who were (are?) the real parents of Michael and Julian and why were the children abandoned to fend for themselves?

It’s not all introspection, of course. Far from it! There’s more than enough blood, guts and ruthless action to satisfy the most jaded of palates. But it all has a purpose to serve.

T. Kingfisher’s novel Swordheart is, as far as I can tell, a stand alone novel. Having said that, I perhaps ought to point out that it is set in the same universe as her novels about the Clocktaur wars (no, that’s not a typo). However I guarantee that you don’t need to know anything about the Clocktaur books in order to fully enjoy this utterly delightful story. I know this is true because I’ve never read any of the Clocktaur books, and yet I absolutely adored Swordheart.

Halla is a 36 year old widow who inherits her great-uncle's estate after he dies. This makes her a rather desirable catch and she comes under great pressure from her aunt to marry a rather clammy-handed and grabby cousin so as to keep her fortune in the family. Halla has no intention of giving in to her aunt’s demands, but nevertheless she finds the situation somewhat overwhelming and in a fit of depression she decides to kill herself. Falling on a sword sounds like a good idea. So she retires to her bedroom, bares her bosom, and takes down an old sword that has hung on the wall since time immemorial. But when she unsheathes it, a man called Sarkis appears.

"I am the servant of the sword," he said. "I obey the will of the—great god, woman, put on some clothes!"

Sarkis has been magically trapped in the sword for centuries and now that Halla has unsheathed him, he is bound to her and is required to guard and save her.

Halla is immediately suspicious:

"Why do you have a sword, anyway?"

He looked down at the blade by his side, then up at her. "To fight with. It’s a sword."

"Yes, but you came out of a sword. It seems redundant."

He stared at her as if she had lost her mind. "I can’t very well wield myself, lady."

Halla begins to wonder if perhaps that might make him go blind, but she decides that it might be rude to ask...

With Sarkis’ help, Halla manages to escape from the clutches of the aunt and the clammy cousin and together they set out on a quest for allies to help her keep her inheritance.

Although Halla is grateful for Sarkis’ protection, it soon becomes clear that she is not without her own resources. She never shuts up – she is constantly asking questions because she genuinely has a desperate need to understand every ramification of every situation. The answers to her questions often send her off on tangents because they invariably remind her of something that once happened to a distant cousin who then… Sometimes she uses this technique as a deliberate ploy with the intention of driving an enemy to distraction (she is very well aware of just how infuriating a chatterbox can be). Often things get quite surreal. When she and Sarkis are stopped on the road by a priest of a dangerous religious sect, she witters at him until he loses interest and goes away:

"... my mother, the human one, she had terrible nerves. Why, a thunderstorm left her completely deranged. She’d take to her bed for days and call for brandy. And cauliflower. I mean, I don’t know why she wanted cauliflower, I’ve never thought cauliflower was a particularly soothing vegetable, but it certainly made my mother happier, so we’d cook it up whenever the weather started to turn. Do you have any cauliflower?"

The cauliflower caper works its usual miracles. Halla and Sarkis escape unscathed from the priest. Until the next time.

The story is nothing but light-hearted froth. However it’s very funny light-hearted froth and that is its saving grace. I was constantly smiling and chuckling. Generally speaking, the humour flows out of the characters rather than the situations and that’s the sort of humour that I like the best. Though having said that, the situations that the characters find themselves in are invariably inventive and sometimes not without a certain surreal humour all of their own. I was particularly taken with the Vagrant Hills. It seems that you never really know where they are because they wander around a lot for their own mysterious reasons. Halla and Sarkis get trapped in them for a while...

After a lot of adventures, it all works out as these kinds of stories invariably do. But that’s irrelevant, of course. It’s the journey that matters, not the destination and this journey is truly a magnificently entertaining one.

Cherie Priest is best known as the author of several first class steampunk stories and a handful of very chilling horror novels. Consequently it came as a bit of a surprise to me when I discovered that her latest novel Grave Reservations is a light-hearted cozy murder mystery with psychic overtones. More than anything, it reminded me of Charlaine Harris’ work in this genre and since there are strong hints in the story that this novel is just the first of a series, I suspect that Cherie Priest may well end up giving Charlaine Harris a jolly good run for her money.

Leda Foley is the self-employed owner of a small travel agency. As the story opens, she is on the phone to one of her clients who is hurrying to the airport to try and catch the plane that he is late for. She reassures him that he has no need to worry. She’s changed his booking to a later flight because she has a bad feeling about the original booking. Naturally, he is very annoyed by her attitude. But his annoyance changes to amazed acceptance when he arrives at the airport just in time to see his original flight burst into flames as it it taxis from the gate to the runway. Leda is psychic and she always pays attention to her odd feelings even though they don’t always mean what she thinks they mean…

The man whose flight she has rearranged is a policeman who is so impressed with her psychic abilities that he asks her to work with him on a very cold case murder that is baffling him. He’s completely run out of ideas. It goes against the grain to ask for help from a psychic, but it is the only avenue of enquiry left to him.

Leda is thrilled to be asked. A few years ago, her fiancée was murdered. The crime was never solved (despite Leda’s psychic input) so perhaps if she helps the policeman with his murder case, he will help her with hers. Mutual back scratching always makes a good story. And naturally, this being the nature of the cozy murder mystery genre, it soon turns out that the two killings are closely connected with each other. Suddenly the game is afoot!!

The bits of business that carry the plot along are what makes books of this kind work (or not, as the case may be), and this novel has them down pat. For example, Leda is trying to train her psychic abilities by performing what she thinks of as Klairvoyant Karaoke – she asks members of the audience at her local bar to present her with objects of great sentimental value and then she attempts to perform a karaoke song to match whatever insight she gains from the object. She is very successful at this. Several times she reduces people to tears when the song she chooses resonates perfectly with the sentiment that lies behind the objects she has been presented with. She finds this pleasing, and it certainly does seem to help train, strengthen and sharpen her abilities. But it leads to trouble because the owner of the bar wants to bill her as a Psychic Psongstress, a title she strongly objects to.

Of course, it would be all too easy for the story to fall into the trap of using Leda’s psychic visions as an unfailing mechanism to untangle the gordion knots of the story. But Cherie Priest is far too wily a writer to fall into that trap. Leda’s psychic insights are all suitably Delphic and often they fail to clarify anything at all – rather they just succeed in making the plot murkier. Consequently the revelations, when they finally appear, arrive naturally from the circumstances rather than from any woo-woo bits of hocus pocus.

I’m greatly looking forward to more stories about Leda Foley. I’m certain that Cherie Priest is on to a winner here.

Covid-19 has been with us for more than two years now and, not unnaturally, it is starting to make itself felt in the books that are currently being published, both fiction and non-fiction.

Killing Time by Stephen Leather is set in a retirement village. Much is made of the effects that covid has had upon both inmates and staff and several significant plot points revolve around the illness. Charlie and Billy live in the village. They pass the time playing dominoes and reminiscing about the good old days when they were both very successful serial killers – successful in the sense that they killed a lot of people, and successful in the sense that they never got caught by the police. But now they are old and weak and helpless. They miss the thrill of the chase, the excitement of the kill. Wouldn’t it be nice to kill again, one last time? One of the nurses in the village is particularly nasty and sadistic. He’d make a good victim…

The story is very cleverly worked out and it is often quite funny in its own rather sick way (Billie and Charlie are really not very nice people but somehow you just can’t help cheering them on). Unfortunately towards the end of the book Stephen Leather loses control of his material and the story degenerates into a conventional thud and blunder chase sequence.

Theroux the Keyhole is Louis Theroux’s lockdown diary. It’s (almost) a day to day account of how he, his wife and his children coped (and sometimes failed to cope) with the strains of isolation. The worry and the stress suffered by the whole family come across very clearly though, this being Louis Theroux, it’s also narrated with a lot of self-deprecating humour which at times is almost unbearably funny. I use the word "unbearably" quite deliberately here because it is always quite obvious that there is a lot of real pain lying not very well concealed behind the jokes. Louis and his wife Nancy argue and fight constantly and acrimoniously, sometimes about very important things. Louis is always quick to point out that these disagreements are usually caused by him being a dick (that’s a direct quote) and he documents each one of them carefully and precisely. Neither Louis nor Nancy coped well with lockdown, and I was mildly surprised when I got to the end of the book to find that they were still together – so many of their disagreements were sufficiently fundamental that I really couldn’t see how they could possibly continue their relationship. In his darker moments, Louis wondered about this as well.

Not only does he document the stresses and strains of his domestic situation, he also turns a very critical eye on how covid has affected the world at large, both at home and abroad. Not unnaturally, he is very critical of the reactions of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson and at times he is quite bitter about the way they consistently failed to rise to the occasion.

Sooner or later, someone will write the definitive history of the covid years. When they do, the thoughts, insights and information recorded in Theroux the Keyhole will doubtless prove to be a very important contribution to it.

In an epilogue, Louis tells us that after a year of lockdown and isolation, when he had finally managed to get himself fully vaccinated and Nancy had been given her first jab, Nancy somehow got infected with covid. His description of the suffering that she endured is harrowing in the extreme, and very painful to read. Because he was fully vaccinated, the infection passed Louis by. Nancy eventually recovered, but for a time it was touch and go…

Stephen Fry approached the lockdown in quite a different way. He saw it as the perfect opportunity to tidy up dusty old cupboards whose doors he had not opened for years. He made many serendipitous discoveries, not least of which was the surprisingly large number of ties that he unearthed. He was well aware that he owned a lot of ties – he’s always been fond of them and he has worn them since he was a small child – but he was rather astonished to find out just how many he did actually own. And each of them sparked some memory or anecdote that he felt needed to be shared with the world. The result is Fry’s Ties, a collection of small essays commemorating his favourite pieces of neckware.

In all honesty, his narration does sometimes come across as rather snobbish. Names like Versace and Gucci fall trippingly from his lips and he spends a lot of time discussing the delights of visiting bespoke tailors in Jermyn Street and the Burlington Arcade. But he does it so disarmingly and what he has to say is so interesting (and so often quite funny as well) that it’s very easy to forgive him.

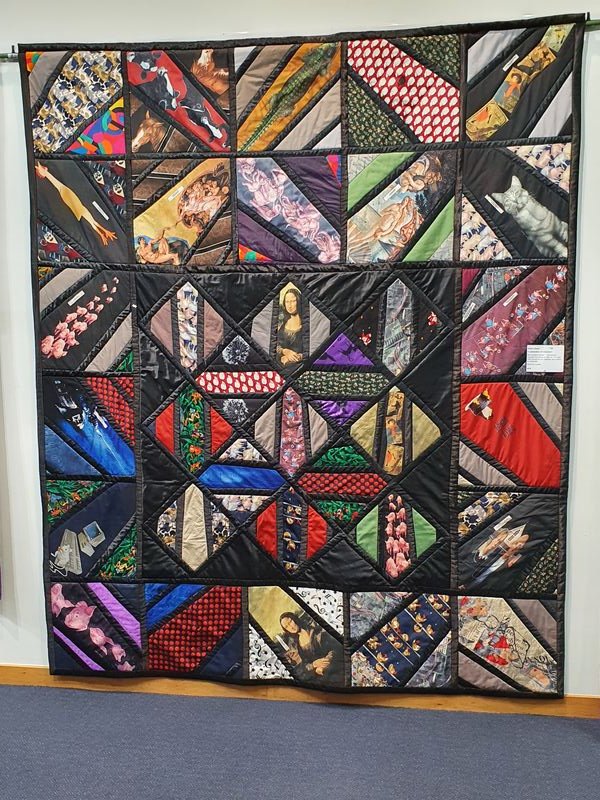

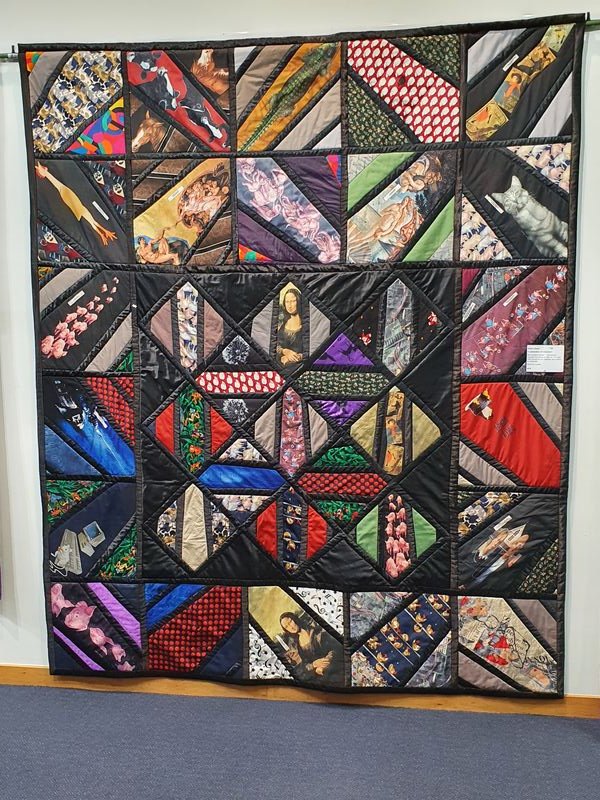

Like many men of a certain age, I too have often had to wear a tie when I went in to the office. Unlike Stephen Fry, I never enjoyed it very much and for the last twenty or so years of my working life I made a point of wearing very silly ties. No Versace for me! You can have my Guccis for garters (assuming you can find any, which you can’t). My ties had pigs and penguins on them, dead chickens, and a flock of white sheep with a single black sheep hiding in plain sight in the middle. I proudly wore Michaelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling, the Mona Lisa, American Gothic and an opticians eye chart. I had a reindeer tie that I wore every Christmas which played Jingle Bells when you thumped it. Wearing ties like these was partly a small act of rebellion, but mainly it was to amuse my students. I always learned the best from my more eccentric teachers and I hoped to have the same effect on my students. I think it worked. I always got lots of approving comments.

After I retired I swore that I would never wear a tie again. When I said this, Robin got a wicked gleam in her eye. "Can I have them?" she asked.

"Of course you can," I said. "But why do you want them? What are you going to do with them?"

"I’m going to turn them into a quilt," she said.

That sounded like a good idea to me, so I gave her all my ties and she turned them into a most magnificent quilt. Here’s a photograph of it:

|

It is no longer physically possible for me to wear a tie. I do not own a single one. So if you want lots of tie anecdotes, pay no attention to me. Go and read Fry’s Ties instead. You won’t regret it.

| John Hart | Down River | Minotaur Books |

| John Hart | Iron House | Thomas Dunne Books |

| T. Kingfisher | Swordheart | Argyll Productions |

| Cherie Priest | Grave Reservations | Atria Books |

| Stephen Leather | Killing Time | Smashwords |

| Louis Theroux | Theroux the Keyhole | Macmillan |

| Stephen Fry | Fry's Ties | Michael Joseph |

| Previous | Contents | Next |